Crafting is Not Just for Kids: How Job Crafting Can Really Impact the Employee Experience

April 7, 2020 in The Consulting Experience

By Haylee Gans

Each month of 2020, we provide insight into what life is like as a consultant by discussing what skills and experiences make this career unique and interesting. While pursuing a graduate degree, a question that constantly plagues exhausted students late at night is: am I really learning anything that’s applicable to the real world? How often do you see organizations truly implementing all of these “best practices”? In industrial organizational psychology (I-O), this is a really important question. I-O psychologists are big fans of something called the “science-practitioner model”, which means that, as the field grows, it is critical that research continues to inform practice and vice versa. One of the best parts of working at FMP for me has been the opportunity to truly see the theory and best practices I learn in school applied to the big bad world of consulting. Just one of these influential topics, and a particular favorite to benefit from in practice at FMP, is job crafting.

Now you may be thinking, what in the world is job crafting, and why are we talking about “crafts” in a consulting blog? Job crafting refers to the personal initiative to personalize your work in an attempt to better match employee needs with organizational resources. The idea of job crafting is rooted in role theory, which suggests that employees with the same job will go about doing their work in different ways and incorporate different tasks. As you can imagine, engaging in job crafting can impact the complexity of a job role, promote or reduce challenges, and increase the meaningfulness of a person’s work.

What does job crafting look like in action? More specifically, job crafting describes the way in which employees customize their jobs by actively changing their tasks and interactions with others. This means that anyone who takes on responsibilities or forms work relationships outside of what is explicitly outlined for their job role is engaging in job crafting of some kind. Beyond just changing the tasks or ways in which you interact with others to get your work done, job crafting can also apply to how you think about your work (the cognitive boundaries of your job). For example, if you focus on the people that you’re helping or the impact that your work has on the environment, that will ultimately influence how you feel about your job and may lead you to experience more of the positive outcomes outlined below.

So, why should you care about job crafting? Whether employee or employer, entry-level or manager, job crafting has important key outcomes that benefit the individual and the organization as a whole. I’ll touch on just a few:

Increased happiness and engagement at work. By taking control over your everyday work activities, the people you interact with, and particularly how you think about your work and its purpose, you can more meaningfully connect to your job. This connection will in turn help you to feel more fulfilled and invested at work.

Increased commitment and performance. Organizational leaders are interested in the bottom line. Job crafting can play a key role not only in improvements in the experience of individual employees, but also in improving outcomes for the organization as a whole. One example is job performance. Intuitively, if you care more about your work, you will try harder at work and be more efficient and effective. Another example is the commitment of employees to the organization. At its core, job crafting is a way for employees to align their own values with the values of their organization. For example, if you value trust and independence, and believe your organization does too, you will feel more dedicated to your company’s mission and goals.

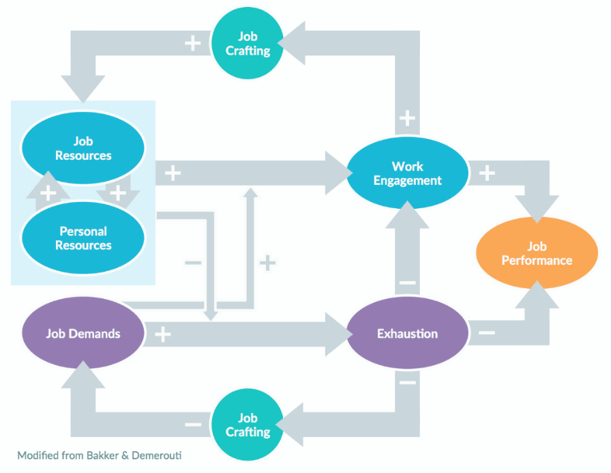

Reduced burnout. How often do we feel exhausted at work? The relationship between burnout and job crafting comes from a theory called the job demands-resources model. By increasing your access to different types of resources at work (e.g., access to different types of projects, social support, and feedback), we can buffer the potential negative impact of high job demands like stress and anxiety that lead to burnout. In addition, trying to eliminate or decrease job demands that actually hinder your ability to work the way you want to (e.g., excess emails), can also help to reduce fatigue from work.

How can job crafting be promoted? So, circling back on the exhausted grad student (not that I have any personal experience in this) – how does FMP foster job crafting, and its subsequent positive outcomes, through their own organizational culture and environment? The key factors are autonomy and teamwork. Instinctively, it makes sense that less interdependence would encourage more job crafting, as you rely less on others. That is clearly not the case at FMP, with our matrixed organizational structure and high levels of collaboration. However, research shows that, if the work environment encourages, or even requires a certain amount of initiative, interdependence can actually support and promote job crafting. Ultimately, “FMPers”, as we affectionately call ourselves, get to work in an environment that promotes job crafting through employee-driven career development, cross-collaboration among technical groups, and high levels of trust and independence. For this grad student, I can truly say that FMP “practices what they preach” in implementing best practice in their own organization, creating a work culture which motivates us and leads to better company-wide outcomes.

Does your organization practice job crafting? Share your thoughts about job crafting with us on LinkedIn!

References:

Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human relations, 65(10), 1359-1378.

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2008). What is job crafting and why does it matter. Retrieved form the website of Positive Organizational Scholarship on April, 15, 2011.

Lu, C. Q., Wang, H. J., Lu, J. J., Du, D. Y., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Does work engagement increase person– job fit? The role of job crafting and job insecurity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(2), 142- 152.

Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, J. R. (2010). Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research. Journal of organizational behavior, 31(2‐3), 463-479.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of occupational health psychology, 18(2), 230.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2015). Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 914-928.

Vogel, R. M., Rodell, J. B., & Lynch, J. W. (2016). Engaged and productive misfits: How job crafting and leisure activity mitigate the negative effects of value incongruence. Academy of Management Journal, 59(5), 1561-1584.

Vogt, K., Hakanen, J. J., Brauchli, R., Jenny, G. J., & Bauer, G. F. (2016). The consequences of job crafting: a three-wave study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 353-362.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of management review, 26(2), 179-201.

Photo Source: https://www.emooter.com/thoughts/balancing-job-demands-resources/